Mono-ha and Minimalism: Postwar Japanese Masterpieces Through the Collector's Lens

As an important expression of Asian post-war minimalism, Mono-ha's concepts and forms not only resonate with Italian Arte Povera in their sensitivity to materials and space but also engage in dialogue with American post-war Minimalism in terms of simplicity, clarity, and conceptual vocabulary.

Emerging in Japan during the 1960s and 1970s, Mono-ha (School of Things) was initiated by a group of young artists who focused on the very existence of materials. Against the backdrop of rapid post-war industrialization, they rejected artifice and returned to "things" and "the relationships between things"—allowing natural forces such as light, gravity, space, and tension to become the protagonists of their works. Regarded as Asia's most representative minimalist art movement, its significance is often paralleled with American Minimalism and Italian Arte Povera, forming three core post-war artistic vocabularies of global collector interest. The recently opened exhibition Minimal at the Pinault Collection in Paris features several classic Mono-ha works, including Sekine Nobuo's iconic installations Phase of Nothingness – Cloth and Stone and Phase of Nothingness – Water, once again highlighting Mono-ha's important position in international art history. On the other hand, the Blum Gallery (now-closed) pioneered the systematic introduction of Mono-ha to the United States as early as 2012 with the exhibition Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha, which later traveled to Gladstone Gallery in New York. Meanwhile, London's Cardi Gallery, which specializes in Arte Povera, presented Tribute to Mono-ha, showcasing the profound resonance between Mono-ha and Arte Povera in terms of materiality, energy fields, and anti-industrial logic, thereby establishing Mono-ha's cross-cultural minimalist intellectual lineage internationally.

Requiem for the Sun- The Art of Mono-ha, installation shots, the Blum Gallery

Tribute to Mono-ha, installation shots, the Cardi Gallery

Sekine Nobuo

Sekine Nobuo is the most symbolic founding figure of Mono-ha. In 1968, his landmark work Phase—Mother Earth announced the birth of the movement—the work itself is not a form but rather the coexistent relationship between object and earth in terms of weight, space, and interface. This radical concept of "constituting art through the very existence of things" established Mono-ha's unique position in global post-war art history.

Phase—Mother Earth is held in the Rachofsky Collection, making it one of the most important Mono-ha benchmarks on the global market. In 2013, the exhibition Parallel Views: Italian and Japanese Art from the 1950s, 60s, and 70s at The Warehouse, organized by Rachofsky, more clearly presented the correspondences and intertextuality between Mono-ha, Arte Povera, Gutai, and other post-war art movements. This exhibition is still regarded as a key moment for Mono-ha's repositioning within a Western context.

Unlike Asian collectors who favor Sekine's late-career gold-leaf series, top European and American collectors focus on his works from the 1960s and 70s, which are giving more focus on the conceptual part. This includes the Pinault family's active acquisition of works such as Phase of Nothingness – Cloth and Stone and Phase of Nothingness – Water, securing Sekine an irreplaceable position within the European minimalist and conceptual art landscape. Consequently, in the contemporary art market, Sekine Nobuo is not only the historical starting point of Mono-ha but also a key figure in pricing, defining, and sequencing Asian minimalist art on the international stage.

Sekine Nobuo, Phase-Monther Earth, 1968

Sekine Nobuo, Phase of Nothingness-Cloth and Stone, 1970-1994

Sekine Nobuo, Phase of Nothingness-Water, 1969

Noriyuki Haraguchi

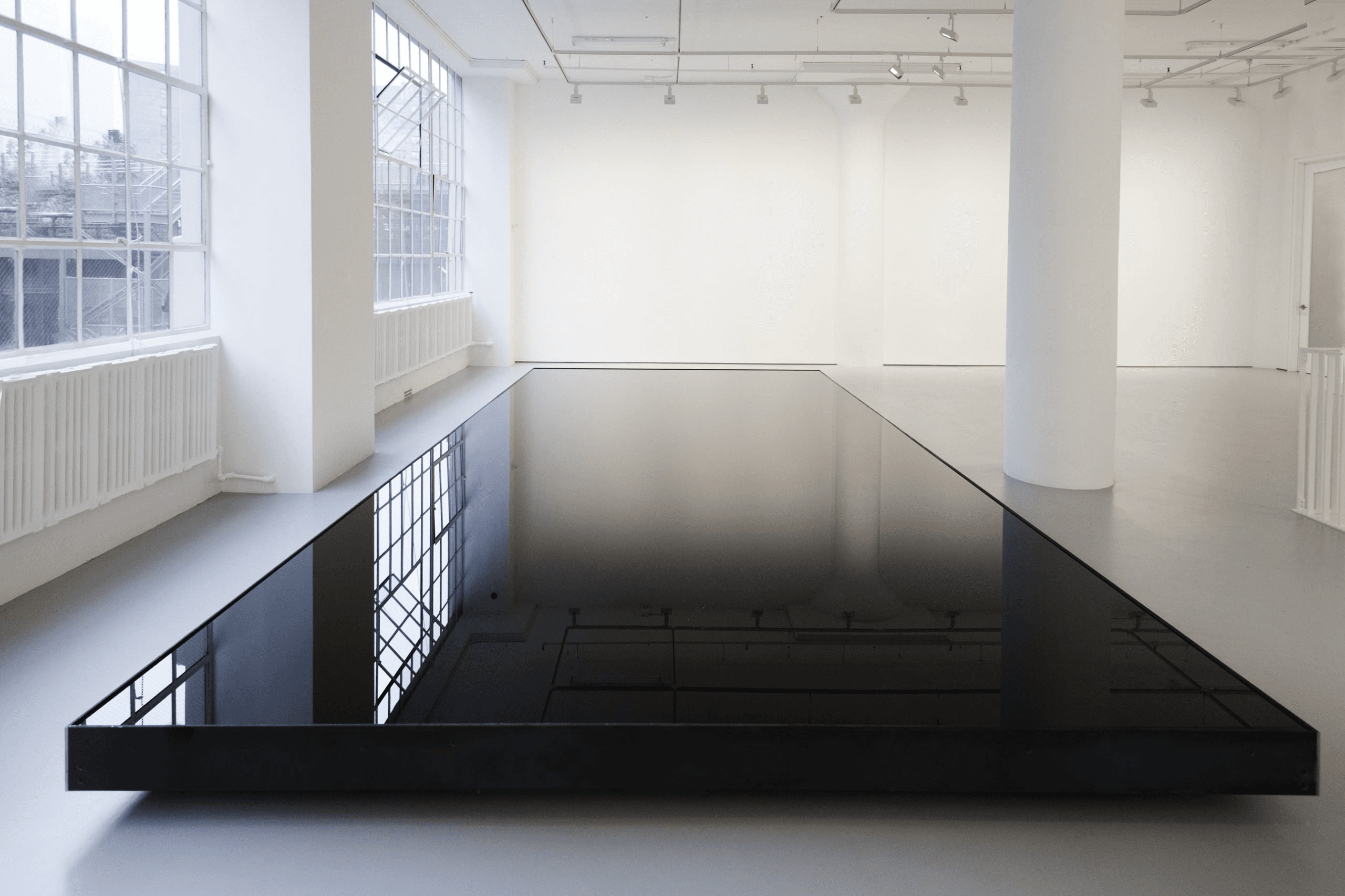

In the historical narrative of Mono-ha, Noriyuki Haraguchi has always been the artist most associated with "industriality" and "material tension." Growing up in Yokosuka, home to a U.S. military base, he began using industrial materials such as steel, oil tanks, and waste machine oil as his artistic language from the 1960s, gradually developing an aesthetic that is both calm and charged with political undercurrents. The work that best represents his core philosophy is Oil Pool, created from 1971 onward. This piece, featuring a black pool of waste oil contained within a welded steel tank, reflects its surroundings like a mirror while possessing an attraction that is almost romantic—yet violent. It led to his invitation to Documenta 6 in Germany in 1977, making him the first Japanese artist to participate, thereby formally entering the map of international art history. This work is now in the collection of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art.

Additionally, Tate in the UK holds his metal sculpture and pipe work Air Pipe, and the Kröller-Müller Museum in the Netherlands collects his later sculptures. These collection directions reveal how Western institutions interpret Haraguchi: he is not merely a branch of Mono-ha but a central figure in post-war material aesthetics concerning "industrial substance" and "spatial reflection."

Haraguchi had already established his status in the American art world with a solo exhibition at MoMA PS1 in New York in 1988. In 2014, Fergus McCaffrey's exhibition Noriyuki Haraguchi in New York comprehensively presented his four-decade-long practice in sculpture and industrial materials, reintegrating him into the international narrative of post-war minimalism and industrial materiality. After his passing in 2020, the Haraguchi Foundation was established, continuing to promote the publication and exhibition of his work, thereby sustaining and even increasing market and academic attention.

Noriyuki Haraguchi, Oil Pool, installation shots at the Fergus McCaffrey

Noriyuki Haraguchi, Air Pipe, 1969

Noriyuki Haraguchi, Black Composition C, 2020

Conclusion

As an important expression of Asian post-war minimalism, Mono-ha's concepts and forms not only resonate with Italian Arte Povera in their sensitivity to materials and space but also engage in dialogue with American post-war Minimalism in terms of simplicity, clarity, and conceptual vocabulary. Sekine Nobuo's sculptures not only demonstrate the tension between objects and space but also, through their intervention in site and immediacy of materials, create interesting connections with American Land Art. Noriyuki Haraguchi's Oil Pool, with its mirror-like oil surface reflecting both space and the viewer, brings to mind Roni Horn's glass sculptures and their subtle capture of light and space; while his works composed of polyurethane cubes, naturally evoke Donald Judd's precise manipulation of geometry and material presence. Limited by space, this article introduces only these two core Mono-ha artists, though many other masters within the movement deserve further discussion. Overall, Mono-ha and Post-Mono-ha have not only expanded the horizons of Japanese minimalism but also, within the context of global collecting and art history, together with post-war Minimalism and Arte Povera, constructed an ongoing, influential cross-cultural dialogue.

Who Can Be Strangers, installation shots, the Blum Gallery